For the previous posts in this series click Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4. This post contains affiliate links. If you make a qualifying purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a percentage of the purchase price.

When I was growing up, we had a newspaper delivered to our home on Sundays. I remember the flyers full of coupons. I would look through the flyers searching for products we use and, when I found one, handing the sheet to my mom so she could cut out the coupon. She kept the cut coupons in alphabetical order in a recipe box with dividers for each letter of the alphabet. When we were grocery shopping, it was almost like a game to figure out which item was a better buy based on combining coupons with items that were already on sale.

My other frugal shopping mentor — The Tightwad Gazette by Amy Dacyczyn (Amazon affiliate link)– also advocated the use of coupons. Despite these stellar early examples, this strategy is one I’ve abandoned at this point in my life and I thought it was worth talking a little bit about why that is.

As always, there’s more than one way to analyze the variables. I have a friend who makes excellent use of coupons and routinely posts on Facebook pictures of her receipts, showing how much she’s saved and spent, along with pictures of the items she bought. I’ve asked her to write a guest post explaining her system. That post will not be ready in time to be part of this series (I only asked her yesterday!), but I will link it here when we publish it. I’m interested to hear what she has to say and find out if there are faults in the analysis I’ve made on this issue!

The World Has Changed

I’m 40-something years old. When I was a child, there were no computers or internet. We got our first home computer when I was in high school and I did not have an e-mail address until my freshman year of college. The only way to get coupons was from flyers in the newspaper, the store sale catalog, or by mailing a letter to companies asking for them.

The Tightwad Gazette (Amazon affiliate link) was mostly written in the pre-and early-Internet era. The book collates newsletters published (and snail mailed to subscribers) from May 1990 to December 1996.

As the world has changed, so have many of the systems and assumptions behind the use of coupons.

No store local to me doubles coupons

When I was a kid, our local supermarket doubled coupons. If the face value was $0.10, you actually got $0.20 off the purchase price. I am not aware of any stores local to me that double coupons. If I’m wrong about that, I’d like to hear differently!

Paper? Hahahahahaha!

I haven’t had a newspaper delivered in years. The last time I checked, which has been many years, the price of a Sunday paper was high enough that the coupons I could get were not enough to cover the cost of purchasing a newspaper. I do not know anyone who has a local paper delivered, so it’s not like I could ask others for the coupons from their Sunday paper.

Privacy

Many people do use coupons and they have to be getting them somewhere. While it’s true that paper isn’t really a thing, the internet is very much a thing and all the resources of the world — including coupons — are available on it.

However, every resource I’ve looked at for coupons requires you to create an account. This includes going directly to the food companies as well as sites that serve as a hub, listing various sales and coupons available on the web.

I am decidedly uncomfortable with the number of accounts I already have on various websites. I recently had a scare where an old account of mine had been hacked. I spent several hours changing passwords on accounts — more than 40 of them. I have never kept a complete list of all the accounts I’ve opened over the years and I’m sure I did not remember all of them. I have no desire to add more accounts, which often means giving the companies permission to contact me (lots of junk mail) and / or sell my data (to whom?), just so I can save a couple bucks on groceries.

Some Things Never Change

Coupons come in two varieties — store coupons and manufacturers’ coupons. No matter who is issuing the coupon, they are doing so for one primary reason: to get money from you.

In the Big Picture, the House Always Wins

Sure, the coupon might save you $0.50 cents on that item, but what about the next time. The manufacturer is betting that you will like their product and will buy it at full price. When a store issues a coupon, they are betting either that you will buy other products too, making up for the $0.50 cents they give you on that one item, or they are betting that in order to get the $10 off your order of $50 or more, you’ll spend $65 when you otherwise would have spent $45. Who hasn’t added a $15 item to their online shopping cart when they only need $5 more to get the free shipping — and the shipping would have been only $5?

The bottom line is that retailers and manufacturers use sophisticated research to manipulate you into parting with your money. If coupons did not benefit them in the long run, coupons would no longer be a thing. Failing to recognize this fundamental truth is like going to Vegas and thinking that the odds are in your favor, not the house’s.

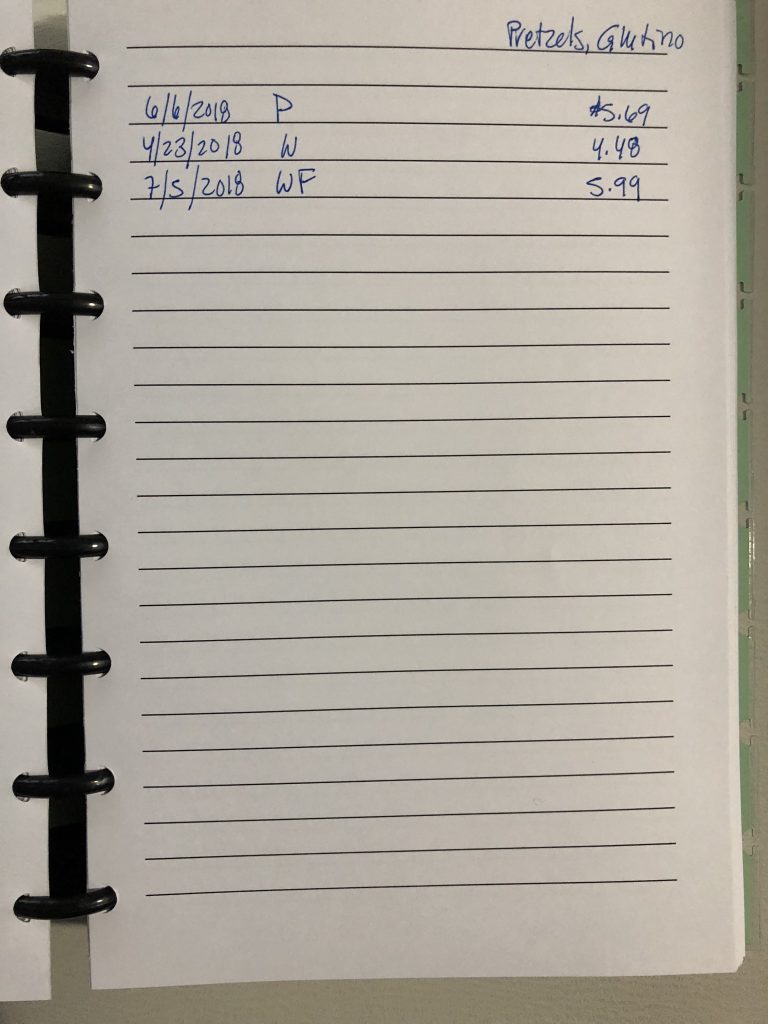

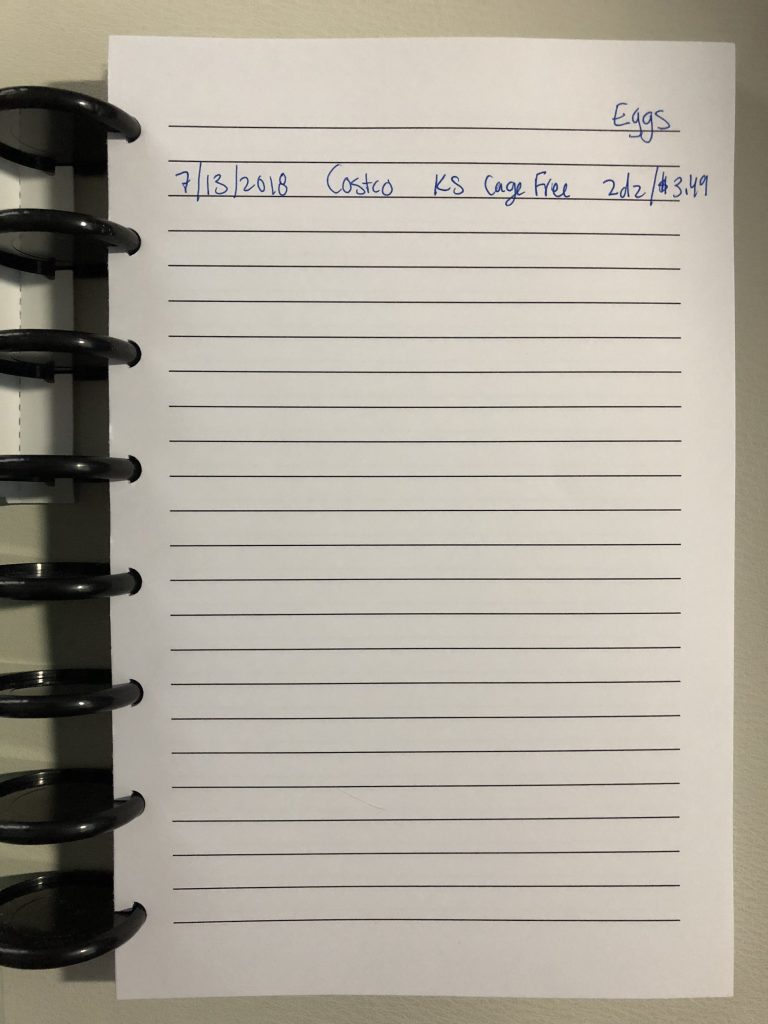

Unlike Vegas, it is possible to beat the odds on a long term basis by failing to fall into some obvious traps when shopping. You don’t have to spend more just because you’ll ‘save’ more off your order. You can choose to purchase a different brand, based on your cold hard data, obtained through unit pricing, your price book, and the other tools which are forthcoming in this series.

Store Brand Products = Name Brand Products?

In general, retailers are not manufacturing the products branded under their name. The products are manufactured by another company and privately labeled for the store. But who is manufacturing the products? Often, it is the name brand company.

For example, in this 2016 interview, Costco CEO Craig Jelinek mentioned that Duracell makes the batteries Costco sells under its Kirkland Signature Brand. If the same company is manufacturing the product, why do Duracell batteries cost so much more than Kirkland Signature batteries? “[Jelinek] explained, ‘Now, this brand here is no advertising, there’s no overhead, there’s just packaging. We don’t advertise it. It’s just a brand.'” The strong implication here is that you are paying Duracell extra money just so they can market their product to you and try to convince you that they are better than all the other battery brands in existence.

Just because the name brand company manufactures the store brand product does not always mean that the contents of the package are identical. Sometimes retailers and manufacturers work out a product formula or parameters and the manufacturer produces to those specifications. In that case, the retailer may have a product that is similar, but not identical, to the brand name products. And sometimes, they only stop the production line long enough to change the packaging. If that’s what they are doing, the store brand and name brand are 100% identical products.

The agreements between retailers and manufacturers are business contracts that you and I aren’t going to get to read. Store brands aren’t labeled with the manufacturer names. As a result, there’s no way for us to know which of the two manufacturing scenarios are true for a particular product.

Fun Detour/

What is important for our analysis here is that it is worth trying out the name brand product. Have some fun and set up a blind taste test for friends and family. I did this recently with butter and we had a lot of fun! Chris, my parents, and I tasted 17 different brands. I was the only one who knew what all of the samples were.

If you want to set up a taste test, buy a variety of brands of the same product, purchasing the smallest quantity you can in order to provide a taste to all the people participating in your taste test. Prepare a plate for each person, with small portions of each brand on the same plate. Label each sample with a number or letter. Write a list for yourself, not to be shared until the end of the event, correlating the anonymous label with the brand.

The food should be eaten in the same manner as you would normally eat it. For example, when we did the butter taste test, I put little pats of butter on the plate. I had bread on the side. We each tasted the butter straight, then spread a little bit on the bread and ate it that way.

Give each person a sheet of paper and a writing utensil so they can make notes as they try each sample. Tell everybody to keep their opinions to themselves until the end, so no one is influencing anyone else as you go. Compare thoughts after everyone has finished trying all the samples.

When we did the butter taste test, I did not do a more involved test, like baking batches of cookies with all the different varieties of butter and taste testing the cookies. This is an avenue you can explore also — how does each brand perform under usual cooking conditions?

When you buy each brand, calculate the unit pricing of the brand. After the taste test, match up the unit pricing with the results from your taste test. How do they compare? /fun detour

Coupons = Brand Names

Coupons are a marketing tool. Store brands have no marketing budget. It is the manufacturers who offer coupons for their brand name products. You’re paying more more for brand names in order to cover marketing costs and they give you back a small portion of that premium price in a coupon.

Coupons = Processed Food

When’s the last time you saw a coupon for carrots? I’ve never seen one. Manufacturers take raw ingredients and turn it into something else, then put a label on it. Consumers don’t know exactly what they did in the process of turning the raw ingredients into something else because that information is usually protected as trade secret. Maybe consumers will like the final product and maybe they won’t.

Manufacturers need us to try the product and like it in order to make money, and therefore they spend money on marketing. Marketing tells us, subtly or not, what we should want and what is best for us, rather than providing us with information so we can make our own value judgments. It is about influencing decisions, by manipulating emotions and beliefs. Marketing is not about providing data. Coupons are one facet of that marketing, designed to make us feel like we are getting a good, whether or not that is empirically true.

It’s true that some produce has brand names on it, but a head of romaine lettuce is pretty much a head of romaine lettuce. You might want to know where the product was grown, if it was grown conventionally versus organically, and whether it is genetically modified. Produce in the United States is already labeled with the first two pieces of data. You have most of the information you need to make a decision, based on your values and dietary requirements. What else could a company try to tell you about their product in order for you to only buy their lettuce, rather than the competing brand’s lettuce?

It is true that there are marketing campaigns for some ingredients. For example, I remember ads for milk or almonds or California raisins. But these campaigns are run by interest groups and are not connected to any specific brand. I don’t recall ever seeing an interest group run a coupon valid for ‘almonds,’ with no brand listed. Again, it is companies who ultimately offer coupons for their specific, brand name products.

My Personal Conclusions

When I weigh the above factors, I have a hard time believing that coupons are going to save our household money in the long run. Buying raw ingredients and making my own foods rather than buying processed foods; purchasing store brands rather than brand names; and purchasing from warehouse stores, online retailers, liquidators, and other alternative sources usually save me more money than coupons can. None of these strategies can be combined with coupons. Coupons are not available for the first two strategies and alternative stores such as those listed in the third strategy usually do not accept manufacturers’ coupons.

There’s only one place where coupons might save me money — combining coupons with sales to stock up on nonperishable household and personal care items like toilet paper and deodorant. We purchase a surprisingly limited number of items in these categories, so I have not taken the time to figure out a good process for handling coupons for them. Instead, I purchase these items in bulk at Costco or on Amazon.

I am looking forward to reading my friend’s forthcoming post on using coupons and will re-evaluate my own choices based on her experiences and process. It’s been a while since I’ve made an evaluation of best practice re: coupons and it may be that my analysis is based on outdated data and beliefs.

Click here for Part 6a: Calculating the Cost of Homemade: Ingredient Costs